Invasive Species

Welcome weeds: How alien invasion could save the Earth

Magazine issue 2795. Subscribe and save For similar stories, visit the Endangered Species Topic Guide Far from ravaging threatened ecosystems, non-native species could be powerful allies in the fight to save them WHEN Ariel Lugo takes visitors to the rainforests of Puerto Rico, he likes to play a little trick. First the veteran forest ecologist shows off the beautiful surroundings: the diversity of plant life on the forest floor; the densely packed trees merging into a canopy high overhead; the birds whose calls fill the lush habitat with sound. Only when his audience is suitably impressed does he reveal that they are actually in the midst of what many conservationists would dismiss as weeds - a ragtag collection of non-native species growing uncontrolled on land once used for agriculture. His guests are almost always taken aback, and who wouldn't be? For years we have been told that invasive alien species are driving native ones to extinction and eroding the integrity of ancient ecosystems. The post-invasion world is supposed to be a bleak, biologically impoverished wasteland, not something you could mistake for untouched wilderness. Lugo is one of a small but growing number of researchers who think much of what we have been told about non-native species is wrong. Aliens, they argue, are rarely as monstrous a threat as they have been painted. In fact, in a world that has been dramatically altered by human activity, many could be important allies in rebuilding healthy ecosystems. Given the chance, alien species may just save us from the worst consequences of our own destructive actions. Many conservationists cringe at such talk. They view non-native species as ecological tumours, spreading uncontrollably at the expense of natives. To them the high rate of accidental introductions - hundreds of alien species are now well established in ecosystems from the Mediterranean Sea to Hawaii - is one of the biggest threats facing life on Earth. Mass extinction of native species is one fear. Another is the loss of what many regard as the keys to environmental health: the networks of relationships that exist between native species thanks to thousands or even millions of years of co-evolution.

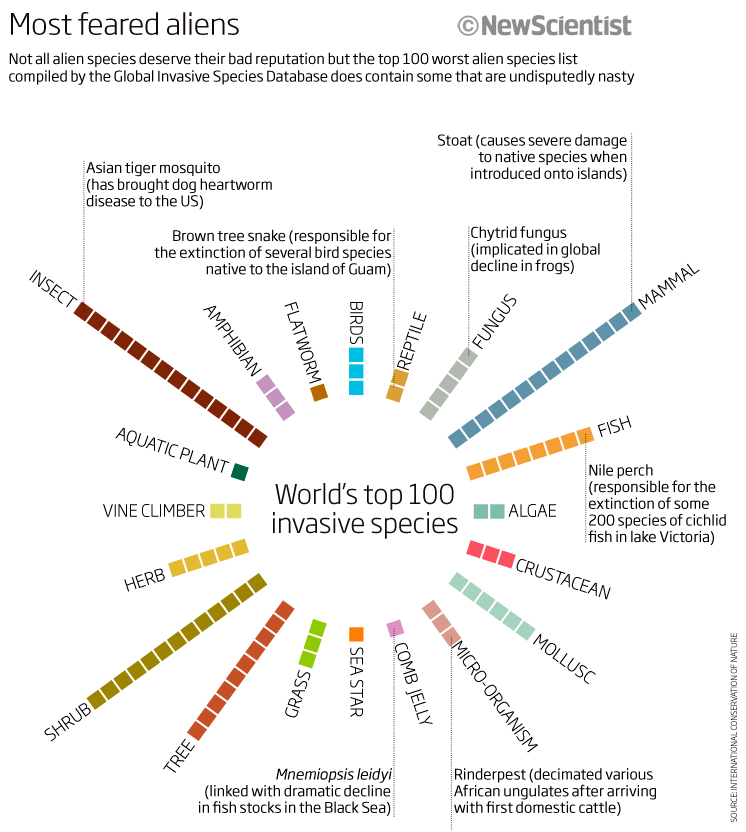

Innocent as charged Advocates for non-native species do not deny that they can sometimes create major problems, particularly in cases where disease-causing microbes are introduced into a new host population. But they argue that often the threat is overblown. For one thing, many species are not nearly as problematic as they are made out to be. Take purple loosestrife, a Eurasian marshland plant frequently listed among the world's worst weeds and the target of multimillion-dollar eradication campaigns. It stands accused of destroying wetlands across North America, where it arrived more than 150 years ago, but there is as yet no documented evidence of any serious damage it has caused. Similarly, the notorious cane toad, introduced into Australia in the 1930s to control pests of the sugar-cane crop, is considered a major threat to the continent's unique fauna. Its highly toxic skin has long been seen as a death sentence for unsuspecting native predators, while its rapid spread is thought to have occurred at the expense of other amphibians. Yet the first serious impact study on cane toads recently concluded that they may in fact be innocent of all charges (New Scientist, 11 September 2010, p 18). Even more surprising is the mounting evidence that many invaders are, in fact, good citizens in their new environments. Salt cedar - a group of Old World shrubs and trees belonging to the same family as the tamarisk - has been shown to provide valuable nesting habitats for birds in the arid American southwest. One of the beneficiaries is the south-western willow flycatcher, an endangered species at the centre of a 30-year, $127 million recovery project. Yet a costly programme to eradicate salt cedar is under way on the basis that it is using up valuable groundwater, though there is no proof that eliminating it will replenish water supplies. In California, Australian eucalyptus trees provide a vital winter habitat for monarch butterflies, a species that has been in dramatic decline for decades due to deforestation in traditional overwintering grounds in places such as central Mexico. The widely loathed purple loosestrife, meanwhile, is favoured by bees, butterflies and waterfowl. These are not isolated examples. In 2006, Laura Rodriguez at the University of California, Davis, published a study of the impact of non-native species. She found that they help natives in many environments and in a variety of ways: by providing new habitats and sources of food, by acting as hosts for organisms to live on and in, and by providing services such as pollination (Restoration Ecology, vol 17, p 177). Art Shapiro, also at UC Davis, has found that 40 per cent of native butterflies in Davis depend exclusively on non-native plants for their survival (BioScience, vol 54, p 182). In the marshlands of southern Spain, red swamp crayfish from the US have become a major food source for birds, otters, turtles and fish, including threatened species that breed and overwinter in the region (Conservation Biology, vol 25, p 1230). There are other less conspicuous benefits. Only once conservationists had eliminated feral cats from Macquarie Island in the south-west Pacific did they realise that these non-native predators had become a vital link in the local food web. Since the last cat was killed in 2000, exploding rabbit populations have eaten much of the island's unique flora bare. Anthony Ricciardi, a biologist at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, is not convinced by these examples. "The current rate of invasion has absolutely no analogue in the geological past. It's a massive experiment that's under way," he says. He argues that it is impossible to tell which invaders will be beneficial and which will be the next Nile perch, which is blamed for wiping out some 200 cichlid fish species in Lake Victoria in east Africa. "We still don't know what the full negative impact of invasive species is because most invasions aren't studied."

No mercy Employing the precautionary principle may sound sensible, but if Lugo and other revisionists are correct, the indiscriminate eradication of aliens is not only unwarranted but could even have detrimental effects. In our fast-changing world, non-native species may be vital in maintaining ecosystem health. "A lot of the reason we've been afraid of exotics is because they are so well adapted for a lot of human-modified conditions and because they have been able to spread so rapidly," says Dov Sax at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. "But these are the same reasons why these species might provide benefits to humans in the future." What happened in Puerto Rico offers a glimpse of how enemies may turn into allies. Once almost completely deforested, this Caribbean island has been the site of a large-scale, unplanned ecological experiment which began in the middle of the last century, when people began abandoning rural landholdings and moved to the cities. At first the results resembled a classic invasion storyline: much of the island was overrun by non-native weeds. However, the dominance of the invaders didn't last. As the decades passed, more and more species began taking root in the understorey. Some were aliens, but many - to the astonishment of observers, Lugo included - were scarce native species. That's not all. When non-native plants were excluded from abandoned pastures, seeds of native pioneers - those that would normally be the first to colonise clearings - did not germinate. The problem was the harsh conditions of the altered habitat, including compacted soil, increased soil temperatures and reduced humidity in ground exposed to the sun, and the presence of ants with an appetite for seeds. Alien species such as the African tulip tree may have ameliorated the situation, improving soil quality as they grew. The non-natives would also have attracted birds and bats whose droppings would have contained viable seeds, including those of native plants. Similarly, the success of nitrogen-fixing exotic trees like white leadtree and white siris may have helped in places where nutrients had been depleted by human activity. "What's happened," says Lugo, "is the introduced species have somehow restored soil and canopy conditions." Today, most of Puerto Rico's new forests support more tree species than its traditional forests, some by as much as 30 per cent. A long list of non-natives - including former plantation crops such as mango, grapefruit, banana, coffee and avocado - have become established in the wild, increasing the island's total tree species count from 547 to 770. What's more, the new forests seem as ecologically sound as the old ones. "We're starting to study nutrient cycling, water-use efficiencies, nutrient-use efficiencies and carbon sequestration, and we don't find much difference," says Lugo. The new forests "function beautifully", he adds. At the very least the experience of Puerto Rico should reassure those who see all aliens as inevitably damaging. "This is not radioactive waste that's coming in," says Mark Davis, a plant ecologist at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota. "They're just species. If they're able to establish, then they'll have ecological functions just as native species will." It also suggests that invasion is part of a natural process of adaptation and reorganisation that is an unavoidable side effect of expanding human activity. "We've created completely new environments," says forest ecologist Jack Ewel at the University of Florida in Gainesville. "When you create a new physical environment, it's no surprise that a new suite of organisms proves to be better adapted to it than what was there before." So how can we use these insights? Some conservationists are tentatively considering using non-native species to fill ecological niches left vacant by extinct natives. However, the complexity and uniqueness of ecosystems means such tinkering is a risky business. Sax and Ewel acknowledge that the introduction of new species can backfire. But they want an end to an all-out war on alien species that increasingly seems misguided. For one thing, many campaigns against non-natives can themselves cause unwanted ecological surprises, not to mention a huge drain on resources. Fighting invasions with bulldozers and pesticides might also create just the right conditions for more invasions. And focusing on non-native species may divert attention away from more constructive conservation strategies, especially preserving native habitat conditions. "There's been a big emphasis on looking at the negative side of the ledger when it comes to exotic species," says Sax. "But there are exotics that do a better job than natives of providing particular ecosystem services, and we need to start thinking more about the positive side if we're going to make informed decisions." "In many cases, we're cutting ourselves off from a valuable ally," says Ewel. Lugo agrees. "Many of these invasions will probably have a pay-off in the future".

Garry Hamilton is a freelance writer based in Seattle and the author of Super Species: The creatures that will dominate the planet (Firefly, 2010) |

ENVIRONMENTAL DNA evidence is being rolled out on a grand scale in the US to track invasive species, but the nation's legal system is lagging. In mid-2010, Christopher Jerde of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana found DNA from invasive Asian carp in water samples taken from the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. It suggested the fish were beyond an electric barrier meant to stop them reaching the Great Lakes (Conservation Letters, DOI: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2010.00158.x). Yet in December a judge ruled that locks on the canal need not be closed, stating that the evidence was not enough to prove the fish threatened the lake's ecosystem. The US Fish and Wildlife Service disagrees. As part of a programme to spot invasive species in the Great Lakes "we will use environmental DNA with traditional techniques", says project manager Michael Hoff. "It is very sensitive." |

www.nonnativespecies.org |

|

20 January 2011 by Garry Hamilton

20 January 2011 by Garry Hamilton